The

The main purpose of the

As a result of this approach, the

The Main Purpose of Montessori

As stated earlier, the main purpose of the

While most education systems are developed from the adult’s perspective, with milestones set according to adult schedules and expectations,

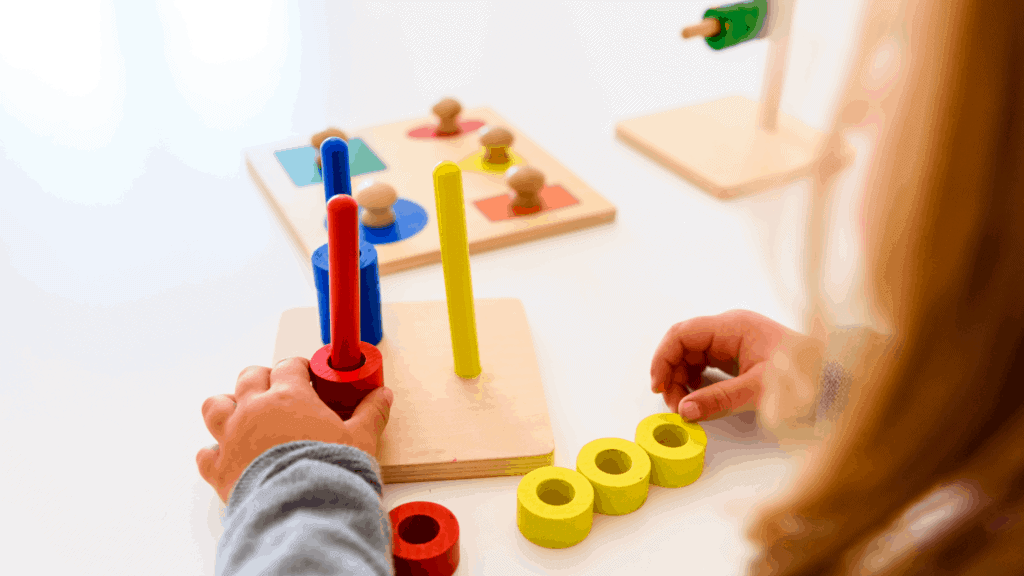

Educators and parents can give children this freedom to learn and develop by preparing a stimulating environment where they can explore and decide which activities they would like to work on.

“We must, therefore, quit our roles as jailers and instead take care to prepare an environment in which we do as little as possible to exhaust the child with our surveillance and instruction. However much the environment corresponds to the needs of the child, by so much will our roles as teachers be limited. We must, however, keep one idea clearly in mind – to give a child liberty is not to abandon him to himself or to neglect him…we must support his development with prudent and affectionate care. Furthermore, even in the preparation of the child’s environment we are faced with a serious task, for in a sense we must create a new world – the world of childhood.“

–MariaMontessori , The Child in the Family

The Beginnings of the Montessori Method

The

Casa dei Bambini came about when Dr.

In the Children’s House, Dr.

“…They were left alone and little by little the children began to work with concentration and the transformation they underwent was noticeable. From timid and wild as they were before, the children became sociable and communicative. They showed a different relationship with each other, of which I have written in my books. Their personalities grew and, strange though it may seem, they showed extraordinary understanding, activity, vivacity and confidence. They were happy and joyous.”

-MariaMontessori ‘s speech on 35th anniversary of Casa dei Bambini

The Casa dei Bambini project was a significant moment in Dr. Montessori’s career as she pivoted from her future as a physician, to one of an educator, upon seeing the difference her observations and methods made on the lives of the children. She believed that this experience with the children was showing her a new way forward in child development, one of following the lead of the child, and this was the beginning of the

Principles of Montessori and how they support the main purpose

The

Respect for the Child

The first principle of

Montessori believed that children should be respected as their own person who has a distinct character and personality from adults. In this sense, respect for the child requires that children be given the freedom to express themselves and explore what interests them within a safe environment.

This principle supports the main purpose of aiding the child to reach their full potential by being attuned to their needs and interests, in a sense, kindling their spirit instead of extinguishing it. This respect will instill confidence in the child, which will help them grow to their full potential.

The Absorbent Mind

Dr.

This principle supports the main purpose by alerting adults that the child needs the proper stimulation and experiences to learn and absorb as much as possible.

“The only thing the absorbent mind needs is the life of the individual; give him life and an environment and he will absorb all that is in it. But, of course, if you keep a camera in a drawer you will never get any pictures. It is necessary for this absorbent mind to go out into the environment. ”

-MariaMontessori , The 1946 London Lectures, p. 65

Sensitive Periods

Montessori education promulgates that there are specific times in a child’s development when they are more attuned to learning a particular set of skills. These are the “sensitive periods”. During this time, children have a natural inclination, attention, and interest where they are committed to learning more about a concept or idea, and exposing them to this would result in better absorption of knowledge.

This principle supports

The Prepared Environment

The

“When we speak of “environment” we include the sum total of objects which a child can freely choose and use as he pleases, that is to say, according to his needs and tendencies. A teacher simply assists him at the beginning to get his bearings among so many different things and teaches him the precise use of each of them, that is to say, she introduces him to the ordered and active life of the environment. But then she leaves him free in the choice and execution of his work.”

MariaMontessori , The Discovery of the Child, p. 65

This principle supports

Auto education

Auto education, otherwise known as self-education, is the

This principle supports the main

Education demands, then, only this: the utilization of the inner powers of the child for his own instruction. Is it possible? It is not only possible, it is necessary. Attention must be stimulated gradually in order to develop the powers of concentration. One must begin with objects that appeal to the senses, that are easily recognizable and that will interest the children: cylinders of various sizes and of colors arranged according to the spectrum, various distinct sounds, rough surfaces that are recognizable by touch. Later we introduce the alphabet, writing, reading, grammar, and design, more complex operations in mathematics, history and science. This is how the child’s knowledge is built.

-MariaMontessori , The Child in the Family

Applications in Modern life

Because the

Today’s children have the benefit of being seen and heard, with expression of their opinions and feelings being encouraged. Respect for the child has gone from a groundbreaking concept to a moral and legal obligation.

Respect for the Child

Practically, respect for the child is shown by allowing them to make choices about the work they would like to do. It also means recognizing that they would know when they are ready and capable to try things, and when they are tired or sleepy. It is the same respect we give adults that

The Absorbent Mind

Because the child’s mind absorbs anything and everything, it would be good to expose the child to varied and interesting experiences that are related to all their senses so that they can learn more. Also, helping the child absorb the information not by telling them about it but by asking them what they think about it.

Sensitive periods

Knowing the eleven sensitive periods and their onset can help the child learn better. The sensitive periods include:

- Movement (birth to one year old) – teaching movement and gross motor skills from

- Small Objects (one to four years old) – allowing children to explore their interest of small objects and details

- Order (two to four years old) – establishing routines, teaching rules and proper place for things

- Grace and Courtesy (two to six years old) – teaching polite behavior

- Refinement of the Senses (two to six years old) – exposing children to sensory experiences so they can learn more about each sense (sight, hearing, touch, taste, smell)

- Writing (three to four years old) – teaching children about letters and number shapes and how to write

- Reading (three to five years old) – teaching children to sound out letters and form simple words (Montessori sometimes combines senses, reading, and writing by teaching children to sound out the letters while tracing a tactile cut-out of the letter so that they learn both form and sound at the same time, and refine their sense of touch)

- Expressive Language (birth to six years old) – teaching words to communication, with emphasis on comprehension

- Spatial Relationships (four to six years old) – teaching children about spaces and places, including direction

- Music (two to six years old) – teaching children about pitch, rhythm, and melody through song and rhyme

- Mathematics (two to six years old) – teaching children about quantity and mathematical operations (addition and subtraction) through the use of concrete materials such as counting beads

The Prepared Environment

To mimic the

The idea of a prepared environment is portable. In experience, prepare for the child’s needs by anticipating what he would enjoy on a day out. For example, during a picnic, bring a ball, a kite, and other items of interest and allow them to choose among them. Pack food items that they would enjoy. The idea is to create a safe and stimulating environment wherever they are so that they can learn by doing things independently.

Auto Education

Hand in hand with the prepared environment, allowing the child to be and do their work in their own space supports the concept of self education. This is done by not interrupting the child’s work or play when they are focused on it. It also means not praising or punishing the child but letting them come to conclusions about what they are learning by themselves.

Conclusion

While